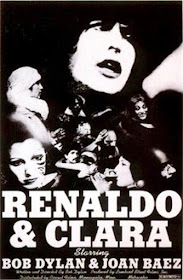

Surveying online remarks

about Renaldo and Clara, the first

(and, to date, last) fictional feature written and directed by legendary

folk-rocker Bob Dylan, provides a sharp lesson in the cult of personality. Had

this amorphous epic been created by some anonymous indie artiste, Renaldo and Clara would have been

relegated to the slag heap of obscurity. Because it was made by Dylan, the

picture is taken very seriously in some quarters, with advocates noting the

influence of Cubist art as well as parallels to the 1945 art-house classic Les enfants du paradis. Whatever. Running

nearly four hours in its original form and comprising a pretentious amalgam of

concert footage, sloppy documentary snippets, and weakly rendered dramatic

scenes, Renaldo and Clara is the

epitome of self-indulgence. Dylan and his famous pals may have had fun shooting

the picture, but the enjoyment does not extend to viewers, except during purely

musical sequences.

To be fair, devoted fans who have spent decades parsing the

mysteries of Dylan’s lyrics will undoubtedly find much to analyze here—Dylan

appears as himself during performance scenes; plays a character named “Renaldo”

in fictional bits while his real-life wife at the time, Sara Dylan, plays his

love interest, “Clara”; and rock musician Ronnie Hawkins plays a character

named “Bob Dylan” in vignettes with actress Ronee Blakeley as “Mrs.

Dylan.” Also featured are the peculiar affectations of the Rolling Thunder

Revue, the notorious Dylan tour that’s featured in concert scenes, so whenever

Dylan sings tunes including “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Knockin’ on Heaven’s

Door,” he wears either masks or white face paint. Because, like, you know, man,

the Dylan onstage is not the Dylan offstage, but even, like, you know, man, the

Dylan offstage isn’t the real Dylan, you dig? To note that Dylan’s rumination on the complexities of public identity could have been articulated more succinctly

is to offer a profound understatement. Except for those who are heavy into

Dylan’s mythmaking, Renaldo and Clara

will seem utterly interminable. Nonmusical scenes ramble on forever without any

sense of purpose, Dylan and his musical friends deliver lifeless performances,

and the real actors sprinkled through the piece—including Sam Shepard, credited

with cowriting the script, and Harry Dean Stanton—struggle through

uninteresting scenes that seem at least partially improvised. The only saving

grace of the movie, unsurprisingly, is the power of music. Dylan is in great

form, as are Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, and others. (The less said about Beat

poet Allen Ginsberg’s musical contributions, the better.)

Renaldo and Clara was brutalized by critics during its initial

release, causing Dylan to largely withhold the film from subsequent public

exhibition, with the exception of a re-release showcasing a two-hour edit that

dumped most of the dramatic scenes. On some level, the movie is harmless in

that it represents a boundlessly creative artist trying something new and

asking his fans to come along for the ride. And yet on another level, one fears

that Dylan envisioned himself as a naturally gifted filmmaker—because, let’s

face it, he was asking for trouble by opening the movie with the song “When I

Paint My Masterpiece.” Points for self-confidence!

Renaldo and Clara: LAME

No comments:

Post a Comment