Things get

weird fast in The Sporting Club, a

wildly undisciplined adaptation of a novel by Thomas McGuane, who later became

a screenwriter of offbeat films with Western themes. Here, the theme is

actually Midwestern, though The Sporting

Club certainly has enough eccentrics and iconoclasts to resonate with other

films bearing McGuane’s name. The basic story is relatively simple. Rich white

people gather at the Centennial Club, a hunting lodge in the Great Lakes region,

for a drunken revel celebrating the club’s hundredth birthday. One of the

club’s youngest members, an unhinged trust-fund brat named Vernur Stanton

(Robert Fields), has a scheme to destroy the club from within while making a

grand statement about class divisions in American society. Vernur fires the

club’s longtime groundskeeper and hires a volatile blue-collar thug as a

replacement, injecting a dope-smoking X-factor into the uptight culture of the

Centennial Club. Yet the plot is only the slender thread holding the

movie together. More intriguing and more prominent are myriad subplots, as well

as bizarre satirical scenes featuring the aging members of the Centennial Club

devolving into savagery.

If it’s possible to imagine a quintessentially

American film that should have been directed by British maniac Ken Russell, The Sporting Club is that movie. Like

one of Russell’s perverse freakouts, The

Sporting Club puts a funhouse mirror to polite society, revealing all the

grotesque aspects that are normally hidden from view. And like many of

Russell’s films, The Sporting Club

spirals out of control at regular intervals.

Here’s a relatively innocuous example. Early in the

picture, Vernur and his best friend, James Quinn (Nicolas Coster), wander from

the Centennial Club to a nearby dam, where the (unidentified) president of the

United States makes a public appearance. Vernur and James sneak onto a tour bus

left empty by Shriners watching the president, then trash the bus and

commandeer it for a presidential drive-by during which Vernur moons the

commander-in-chief. The scene raises but does not answer many questions related

to character motivation and logistics. And so it goes throughout The Sporting Club. Outrageous things

happen, but it’s anybody’s guess what makes the people in this movie tick or

even, sometimes, how one event relates to the next. Very often, it seems is if

connective tissue is missing. In some scenes, James makes passes at Vernur’s

girlfriend, and in other scenes, he’s involved with the local hottie sent to

clean his lodge. Huh? And we haven’t even gotten to Vernur’s fetish for vintage

dueling pistols, the time capsule containing century-old pornography, or the

climactic scene involving a machine gun and an orgy.

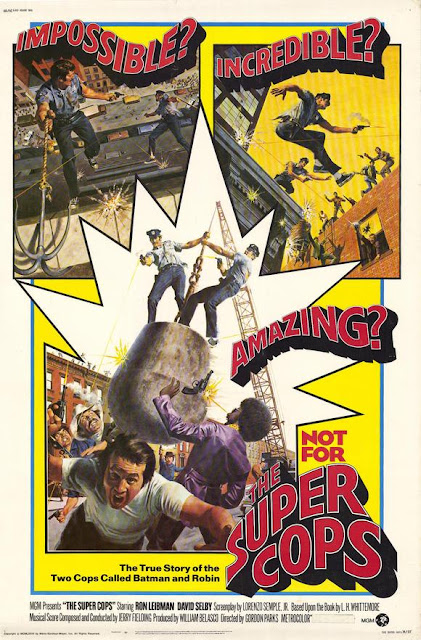

As directed by journeyman

Larry Peerce and written by versatile wit Lorenzo Semple Jr., The Sporting Club has several deeply

interesting scenes and a few vivid performances. Coster, familiar to ’70s fans

as a character actor, does subtle work in the film’s quiet scenes, even

though the nature of his overall role is elusive. Conversely, the great Jack

Warden is compelling to watch as the replacement groundskeeper, even though

he’s spectacularly miscast—more appropriate casting would have been Kris

Kristofferson, who plays a similar role in the equally bizarre Vigilante Force (1976). The lively ensemble also includes Richard Dysart, Jo Ann Harris, James Noble, and Ralph Waite.

There’s a seed of something provocative hidden inside the bewildering action of

The Sporting Club, and one imagines

the folks behind the movie envisioned a provocative generation-gap farce. What

they actually made is a disjointed oddity with lots of drinking, sex,

violence, and pretentious speechifying.

The Sporting Club: FREAKY