Whereas some of his peers

in the French New Wave were provocateurs who blended experimental techniques

with radical politics (here’s looking at you, Monsieur Godard), Eric Rohmer

took a different path. Crafting cerebral character studies bereft of cinematic

fireworks, Rohmer was something of an essayist for the big screen, using

copious amounts of dialogue and/or voiceover to explore the foibles of

humankind. Throughout his career, Rohmer made groups of films that he linked

with series titles, and the first such group was called Six Moral Tales. Commencing with a short film titled The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1963), Six Moral Tales concluded with Rohmer’s

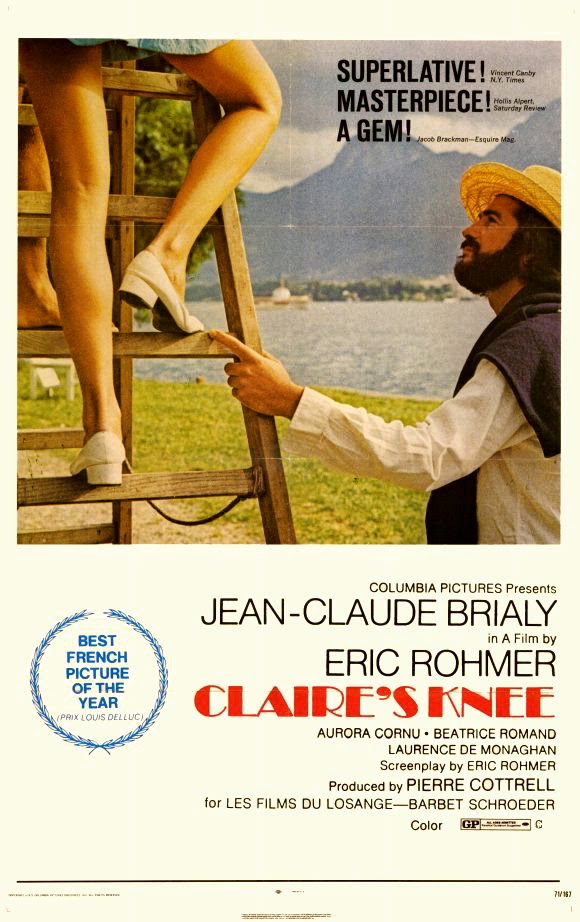

first two features of the ’70s, Claire’s

Knew and Chloe in the Afternoon. (The

latter picture is sometimes titled Love

in the Afternoon.) Both movies investigate questions of love and sexuality

through the prism of men tempted by inappropriate women.

In Claire’s Knee, the better of the two

pictures, a wealthy diplomat named Jerome (Jean-Claude Brialy) encounters a

long-lost female friend named Aurora (Aurora Cornu) during a vacation in

picturesque Lake Annecy. Although Jerome has a girlfriend, Aurora persuades

Jerome to help with an experiment that she hopes will stimulate ideas for the

novel she’s trying to write. Aurora asks Jerome to flirt with Laura (Béatrice

Romand), the teenaged daughter of a mutual friend, in order to see whether

Laura takes the bait. Jerome, who is accustomed to doing well with women,

agrees partially because the experiment sounds intellectually stimulating and

partially because the idea of a tryst with an attractive young woman is

tantalizing. Yet plans go awry once Laura’s cousin Claire (Laurence de Monaghan)

arrives in Lake Annecy. Unlike the dark and quirky Laura, Claire is a gleaming

blonde, so Jerome becomes obsessed with Claire.

More specifically, as the title

suggests, Jerome’s preoccupation fixates on Claire’s knee because Jerome sees

Claire’s unworthy boyfriend touching her knee while giving her a line about how

he’ll always be true. In Jerome’s addled mind, Claire’s knee is the way to her

heart. Claire’s Knee tells an oddly

compelling story that’s filled with unsettling sexual implications, even though

the tone of the piece is clinical. Paralleling Aurora’s endeavor, the whole

film feels like an experiment testing what happens when the heart and the mind

interact. (As Aurora says, “Everyone wears blindfolds or at least

blinders—writing forces me to keep my eyes open.”) The women in Jerome’s life

display various fascinating colors, from Aurora’s playful detachment to

Claire’s youthful arrogance to Laura’s sexy insouciance. In the middle of all

this female energy is Jerome, whom Rohmer uses to represent a prevalent sort of

testosterone-driven entitlement. “When something pleases me, I do it for

pleasure,” Jerome says. “Why tie myself down with one woman when others

interest me?”

Detractors of Rohmer’s restrained style could easily complain

about the static visuals and the absence of a major climax, but Claire’s Knee adroitly captures the

ephemeral feelings that people experience while moving through the intricate

dance of attraction, achieving intimacy at one moment and lapsing into distance

the next. Subtle profundities abound, and Rohmer’s filmmaking is as elegant in

its simplicity as the acting of the expert cast is incisive.

The follow-up

movie, Chloe in the Afternoon, tries

to do more than its predecessor but ends up accomplishing less. The picture

concerns a lawyer named Frédéric (Bernard Vaerley), who is married to beautiful

teacher Hélène (Françoise Verley) but still has a wandering eye. During the

first part of the film, Frédéric explains his shapeless ennui in voiceover: “The

prospect of quiet happiness stretching indefinitely before me depresses me.” Put more bluntly, Frédéric is bored by marriage and preoccupied with the

notion of fresh romantic conquests. Accordingly, he experiences a long fantasy

sequence during which he wears an amulet that robs beautiful women of free

will, giving him endless access to new sex partners. (Many of the actresses

from Claire’s Knee cameo in this

sequence.) Once the story proper gets underway, around 25 minutes into Chloe in the Afternoon, Frédéric

receives a visit from an old flame, Chloé (played by one-named Gallic starlet

Zouzou). In modern vernacular, she’s a hot mess, having spent years bouncing

from job to job and from lover to lover without setting down roots. Frédéric

helps Chloé get back on her feet, and the two steadily advance toward a

tryst—even as Frédéric wrestles with the potential repercussions of

transforming his erotic dreams into reality.

The beauty of Claire’s Knee is that it’s about, at least in part, a man realizing

that his sense of sexual omnipotence is an illusion. The story is palatable

because it humanizes a would-be Casanova. By comparison, Chloe in the Afternoon seems pedestrian and, within the chaste

parameters of Rohmer’s style, déclassé. Beneath the surface of articulate

dialogue and meticulous dramaturgy, it’s a trite tale about a wannabe philanderer

who toys with the emotions of a vulnerable woman. After all, is Frédéric’s

lament that “I take Hélène too seriously to be serious with her” anything but a

trussed-up version of the old saw, “She doesn’t understand me”? Chloe in the Afternoon is a serious and worthwhile rumination on

matters of the heart, but it’s not as novel or provocative as Claire’s Knee.

Claire’s Knee: GROOVY

Chloe in the Afternoon: GROOVY

1 comment:

Just watched both of these and agree that CK is the best of the two (unlike David Thomson, who feels the opposite way, apparently)

But, wow, I guess I just have to say it : Seemed kinda like a "KneeToo" moment to me, haw haw!!

I mean, once he gets going, the dude really goes to town on that knee!

Post a Comment