While the threadbare premise of The Sweet Creek County War was never to be the foundation for singular entertainment, the script’s colorful dialogue and earnest characterizations could have become the building blocks for something highly watchable. Alas, J. Frank James elected to direct his own script instead of entrusting it to more capable hands, thus ensuring the end of a screen career that began just a few years earlier with the other low-budget Western that he wrote and directed, The Legend of Earl Durand (1974). James was not without skill as a screenwriter, but he was hopelessly inept as a director, so both of his films squandered their potential. Even the title of The Sweet Creek County War indicates how badly this piece suffers for anemic execution—although the title suggests a sweeping story about frontier conflict, the picture largely depicts varmints laying siege to a single cabin occupied by the three main characters. More like The Sweet Creek County Skirmish.

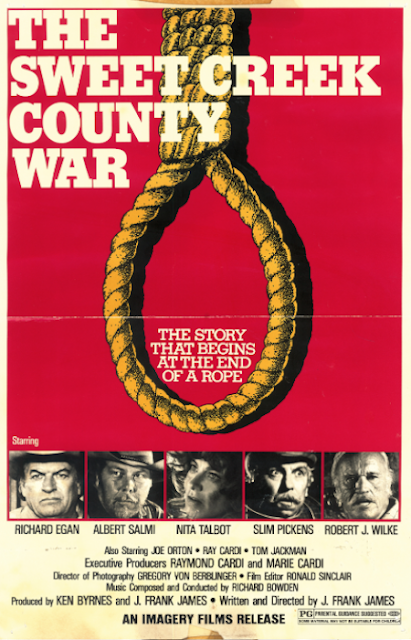

As for those characters, they are retired lawman Judd (Richard Egan), aging outlaw George (Albert Salmi), and past-her-prime prostitute Firetop Alice (Nita Talbot). After Judd rescues George from a lynch mob, the men pool their resources to buy a ranch. Later, George drunkenly marries Firetop Alice and brings her back to the ranch, upsetting the dynamic of his friendship with Judd. Meanwhile, vicious developer Lucas (Robert J. Wilke), who wants the land on which the ranch is located, unleashes gunmen to intimidate Judd and George. Also drifting through the story, somewhat inconsequentially, is a stuttering dope named “Jitters Pippen,” played by Slim Pickens. (Presumably Dub Taylor was unavailable and Strother Martin was too expensive.)

The basic premise of The Sweet Creek County War appeared in countless previous Western movies and TV shows, so the picture’s only moderately individualistic elements are characterizations and the dialogue—and what these elements lack in originality, they offer in sincerity. James seems committed to exploring both an unusual friendship and the conflicted emotions of people who carry deep regrets. Accordingly, had James worked with a proper director, one imagines he could have minimized the script’s formulaic components and leaned into the poignant ones. In turn, improvements to the script and the participation of a competent filmmaker might have attracted relevant performers, no offence to the blandly competent Egan, Salmi, and Talbot. After all, acting isn’t the problem here. The most amateurish aspect of The Sweet Creek County War is unquestionably James’s artless shooting style.

As for those characters, they are retired lawman Judd (Richard Egan), aging outlaw George (Albert Salmi), and past-her-prime prostitute Firetop Alice (Nita Talbot). After Judd rescues George from a lynch mob, the men pool their resources to buy a ranch. Later, George drunkenly marries Firetop Alice and brings her back to the ranch, upsetting the dynamic of his friendship with Judd. Meanwhile, vicious developer Lucas (Robert J. Wilke), who wants the land on which the ranch is located, unleashes gunmen to intimidate Judd and George. Also drifting through the story, somewhat inconsequentially, is a stuttering dope named “Jitters Pippen,” played by Slim Pickens. (Presumably Dub Taylor was unavailable and Strother Martin was too expensive.)

The basic premise of The Sweet Creek County War appeared in countless previous Western movies and TV shows, so the picture’s only moderately individualistic elements are characterizations and the dialogue—and what these elements lack in originality, they offer in sincerity. James seems committed to exploring both an unusual friendship and the conflicted emotions of people who carry deep regrets. Accordingly, had James worked with a proper director, one imagines he could have minimized the script’s formulaic components and leaned into the poignant ones. In turn, improvements to the script and the participation of a competent filmmaker might have attracted relevant performers, no offence to the blandly competent Egan, Salmi, and Talbot. After all, acting isn’t the problem here. The most amateurish aspect of The Sweet Creek County War is unquestionably James’s artless shooting style.

The Sweet Creek County War: FUNKY

1 comment:

Nice

Post a Comment