Cheering Section: LAME

Thursday, November 3, 2022

Cheering Section (1977)

Cheering Section: LAME

Friday, October 21, 2022

The Bride (1973)

Whereas many low-budget horror filmmakers realize the trick to circumventing anemic production values is to shoot most scenes outdoors and/or at night, the storyline of The Bride requires the majority of scenes to happen indoors, which accentuates the cheap quality of the camerawork and sets. Even worse, the storyline requires lots of scenes featuring just one actor (the person being tormented at any given moment), and the players in The Bride lack the magnetism needed to hold viewers’ attention. Not helping matters is the script’s reliance on repetitive moments and overextended wannabe suspense beats. Need it be mentioned that the filmmakers succumb to desperation by inserting a protracted dream sequence? The middle of the picture is rough going, and it’s not as if the beginning and end are strong. Nonetheless, the core of this piece offers something akin to a feminist statement (until that statement gets undercut by the twist ending), and some credit is due for the filmmakers’ restraint in terms of sex and gore. Anyway, someone felt this movie had exploitable elements because it was re-released under at least two alternate titles: The House That Cried Murder and Last House on Massacre Street.

The Bride: FUNKY

Thursday, September 1, 2022

The Spiral Staircase (1975)

Helen (Bisset), who lost the ability to speak after witnessing a tragedy, works as a caregiver for the elderly matriarch of a wealthy family that includes brothers Joe (Plummer) and Steven (John Phillip Law). Meanwhile, a local serial killer preys upon women with disabilities, triggering fear that Helen might be next on the hit list. Instead of focusing on that intrigue, screenwriters Chris Bryant and Allan Scott (wisely hiding behind a shared pseudonym) and director Peter Collinson lumber through aimless scenes about a drunk cook and a love triangle comprising the brothers plus comely secretary Blanche (Gayle Hunnicut). Most of this material is insipid, nonsensical, or both, and dopey sequences involving mysterious figures scuttling about in nighttime rain provide only brief reprieves from tedium. The Spiral Staircase finally gets down to business in the last 40 minutes or so, with attacks and chases and killings, though it’s pointless trying to track or understand the behavior of anyone onscreen. Still, Bisset is suitably alluring and Plummer is suitably pompous, so at least the movie delivers for fans of those actors. Similarly, Collinson and cinematographer Ken Hodges render lively compositions full of ominous foreground objects and shadowy background spaces, so The Spiral Staircase has the look of a passable shocker.

The Spiral Staircase: FUNKY

Tuesday, August 30, 2022

Hard Knocks (1979)

By the late ’70s, actor Michael Christian had spent a decade struggling to capitalize on the minor notoriety he gained from a recurring Peyton Place role—hence this would-be star vehicle, which the fading actor wrote and produced. Alas, the story he contrived was never likely to attain mainstream acceptance. You see, Christian cast himself as a Hollywood gigolo who freaks out after getting abused by a sadistic john, then flees to the countryside, where he befriends a kindly grandfather and a verging-on-womanhood teenager. The first half-hour of the movie is arrestingly sleazy, with disco music throbbing over montages filled with full-frontal nudity; the middle of the film is as gentle as a Disney picture; and the climax, featuring Christian’s character getting chased by trigger-happy cops, is overwrought B-movie pulp. The differing tonalities of the movie’s three sections clash so harshly that Hard Knocks—which has also been distributed as Hollywood Knight and Mid-Knight Rider—is a thoroughly confusing cinematic experience.

When viewers meet him, Guy (Christian) is caught in a dangerous rut, turning tricks primarily for older female clients but occasionally getting beaten by men who don’t like how he earns his money. When an encounter with rich clients in Beverly Hills turns ugly, Guy loses his cool and beats one of the clients nearly to death, then skips town rather than face consequences. The fugitive gigolo finds shelter on a farm occupied by Jed (Keenan Wynn) and Jed’s granddaughter, Chris (Donna Wilkes). A kind of surrogate family takes shape until a bar brawl lands Guy in jail—which, in turn, leads the local sheriff to connect Guy with police reports about the Beverly Hills incident.

Had a better writer polished the raw materials of Christian’s lurid storyline, something coherent might have resulted—because despite the overall clumsiness of this picture’s execution, there’s an interesting core pertaining to the malaise of a character who can’t decide whether he’s cheapened his soul beyond redemption. It’s also a bummer to report that Hard Knocks gets worse as it progresses. The last section is predicated on sketchy character motivations, and the middle section gets so dull that at one point the film stops dead for a “comical” montage of Christian and Wynn riding a sidecar motorcycle. Still, what makes Hard Knocks impossible to completely dismiss is that rough first section, released months before the immeasurably better American Gigolo (1980). The sex-work stretch of the picture is dark, grimy, and sad, powered by affectless voiceover and pulsing musical rhythms. As rendered by director/cinematographer David Worth, this stuff isn’t good filmmaking, per se, but it’s vividly grungy.

Hard Knocks: FUNKY

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

Three Warriors (1977)

Demonstrating that the contributions of a single artisan can improve even the shabbiest material, this Native American-themed outdoor adventure is disposable but for resplendent cinematography by the great Bruce Surtees, who imbues every shot with depth and weight, achieving especially beautiful results during lengthy sequences set in high-altitude forests. (There’s a reason Surtees was Clint Eastwood’s go-to DP for several years.) So even though Three Warriors presents an unrelentingly trite narrative, and despite director Kieth Merrill’s unsure way with actors, the movie is visually rewarding from its first frame to its last. Also worth noting, of course, is the filmmakers’ commitment to celebrating the Native American experience and to showcasing minority performers.

The story revolves around Michael (McKee “Miko” RedWing), an Indian teenager who lives with his mother and siblings in Portland. The kids’ father died years earlier, a tragedy that hangs over the whole storyline. The family treks to their old home, Warm Springs Indian Reservation, for a visit with Grandfather (Charles White-Eagle), who is committed to living as traditionally as possible. Initially, Michael is angry and sullen about spending time in the country, but when Grandfather takes Michael on an outdoor journey that has perilous aspects, the boy learns to respect his heritage. Specifically, Grandfather buys Michael a seemingly lame horse, then guides Michael through nursing the animal back to health. Adding contrived tension is a subplot involving a poacher (Christopher Lloyd) who regularly invades Indian land to capture and slaughter wild mustangs. There’s also some comic-relief material involving a newly arrived park ranger (Randy Quaid) who struggles to bond with Native Americans.

Everything that happens in Three Warriors is predictable, so the first half of the picture is slow going, especially because Michael is portrayed as such a petulant little twit that it’s unpleasant to watch his incessant tantrums. Yet once Michael’s transformation begins, Three Warriors shifts gears by focusing on lively shots of regal animals and magnificent locations. The sequence in which Michael captures an eagle’s feather (yes, that old cliché) is enjoyable because of its meticulous detail, and the final showdown with the poacher generates mild excitement. RedWing never made another movie and White-Eagle has a thin filmography, so that speaks to their limited skillsets. Quaid is somewhat appealing while Lloyd provides drab one-note villainy. In lieu of acting firepower, the movie has Surtees’ expert camerawork and the keen visual sense of director Merrill, best known for his Oscar-winning doc The Great American Cowboy (1974).

Three Warriors: FUNKY

Sunday, August 14, 2022

Stop! (1970)

While Stop! is occasionally (and deliberately) cryptic, the film overflows with mood. Gunn and cinematographer Owen Roizman employ striking compositions, some quite melodramatic, so every shot feels like a piece of an art installation. The leading actors are all lean and pretty, allowing Gunn to use the angles and surfaces of the human body like colors in a painting, especially during atmospherically filmed sex scenes. (Despite the X rating, nothing explicit is shown.) Gunn also employs trippy editing techniques, from the predictable (languid montages set to ominous music) to the unpredictable (splices that render unclear who is having sex with whom). And while the dialogue can tend to be obvious and stilted (“I really think I love you—I don’t know”), Gunn renders several memorably weird moments of human interaction. The vignettes involving a prostitute are as humane as they are unflinching, and the scene during which Lee paints her husband’s toenails while he makes out with Clark’s character feels personal and real.

Yet the test of a piece like Stop! is not its ability to command attention with glossy images and alluring flesh, but rather its ability to explore heavy concepts. A superficial reading of Stop! would interpret the title literally, thus positioning the picture as Gunn’s plea for people to transcend psychosexual gamesmanship. However it seems unlikely Gunn was after anything that reductive or tangible. Note, for instance, the centrality of mental illness and sexual identity. Does every story about a lost soul need to end with a definitive moment of self-discovery? Clues regarding the answer to that question may be found in the picture’s bold final shot, which won’t be spoiled here. Among other things, Stop! is a descent into the unknowable—so for some viewers, the final shot might seem like a cop-out, while for others, the image could be the perfect grace note. Perhaps the highest compliment one can offer Gunn’s little-seen debut is to call it a mosaic that reveals as much about the beholder as it does about itself.

Stop!: GROOVY

Tuesday, August 9, 2022

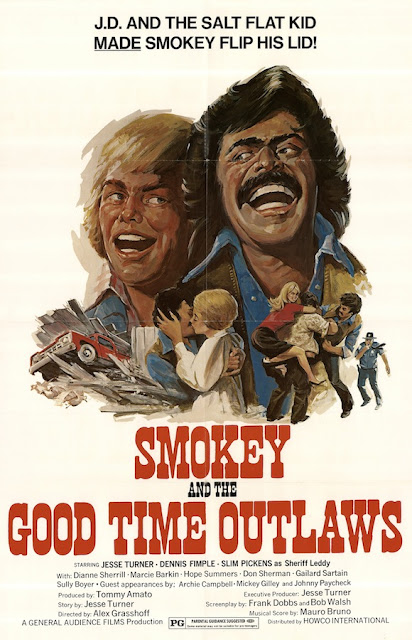

Smokey and the Good Time Outlaws (1978)

Here’s a peculiar one. About one-third of Smokey and the Good Time Outlaws is exactly what viewers might expect, a shameless riff on a certain Burt Reynolds blockbuster. There’s even a subplot about a woman running from the son of a vulgar sheriff. Yet the other two-thirds of Smokey and the Good Time Outlaws comprise an inept but sincere music-industry saga told from the perspective of someone with real-world experience. Jesse Lee Turner—the executive producer, cowriter, and star of this flick—enjoyed a minor novelty hit with the 1959 song “Little Space Girl” before his recording career sputtered. Presumably the goal of this enterprise was to get things going again, so the film features Turner performing several original songs.

The picture opens in a tiny Texas town where ne’er-do-wells J.D. (Turner) and the Salt Flat Kid (Dennis Fimple) dream of showbiz success. J.D. is a singer-songwriter while the Kid is both J.D.’s accompanist and a ventriloquist. In jail after a bar brawl, the guys meet a fellow inmate who claims to be a music manager. Before he skips town, the “manager” scams cash from the guys and offers a business card they believe is their ticket to success. Off to Music City they go. Along the way they meet two ladies, one of whom is being pursued by Sheriff Leddy (Slim Pickens). The movie makes quick work of the ensuing Burt Reynolds-style high jinks before devoting much more screen time to the rigors of pursuing fame in Nashville. The guys hook up with a real manger, albeit a sketchy one, and they find allies in empathetic locals. Inevitably, the story climaxes with a make-or-break concert.

Even though Smokey and the Good Time Outlaws is amateurish, the story is coherent, the leading actors are as enthusiastic as their characters, and the content is more or less family-friendly. In other words, the picture is wholly innocuous—except for some iffy flourishes. We’re talking a chase scene featuring “The William Tell Overture,” a major subplot (the girls and the sheriff) that completely disappears, and the truly bizarre spectacle of J.D.’s stage persona. While singing, Turner crouches and gyrates and twists as if he’s being electrocuted. Naturally, on-camera audiences pretend to be driven wild by his antics. Yet Smokey and the Good Time Outlaws—which has also been exhibited as Smokey and the Outlaw Women and J.D. and the Salt Flat Kid—is more of a curiosity than anything else inasmuch as it documents a stage in Turner’s odd trajectory. At some point after the movie faded from view, he shifted from entertainment to evangelism, though he eventually blended his interests by recording Christian albums. More recently, Turner has proselytized for the MAGA movement.

Smokey and the Good Time Outlaws: FUNKY

Monday, August 1, 2022

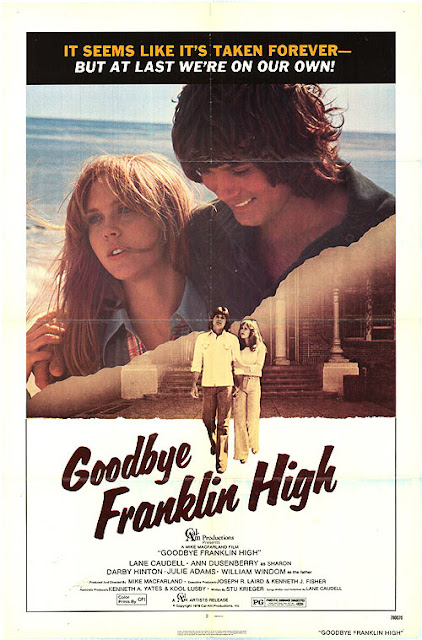

Goodbye, Franklin High (1978)

Will’s dad (William Windom) has a dangerous case of emphysema, and Will’s mom (Julie Adams) may be having an affair. Given these complications, Goodbye, Franklin High occasionally threatens to become a real movie instead of a trifle. That it never makes this leap is attributable equally to the shortcomings of Krieger, MacFarland, and leading man Lane Caudell. Giving a performance as deep as a Donny Osmond song, Caudell tries to express big-time anguish but never seems more upset than a kid whose ice-cream cone just fell on the ground. Caudell’s youthful costars—Darby Hinton, as Will’s buddy, and Ann Dusenberry, as Will’s girlfriend—render equally bland work, though one gets the sense this production lacked the resources for multiple takes. Screen veterans Adams and Windom achieve something closer to credibility, especially during a sequence in which the protagonist’s family addresses the rumored infidelity of Adams’s character.

Goodbye, Franklin High: FUNKY

Saturday, July 16, 2022

6 Million Views!

Hey there, groovy people! Checking in to say how gratifying it is that Every ’70s Movie continues to attract eyeballs four (!) years after daily posting concluded. Recently I’ve happened upon a few more obscure features, so reviews of those movies will get posted in the coming weeks, along with continued selections from the wild world of ’70s telefilms. Although theatrically released narrative features remain the focus of this blog, so many interesting—or at least entertaining—things happened on the small screen during the ’70s that it’s fun to explore that space now that my list of unseen ’70s theatrical features contains less than 500 movies, many of which seem to have disappeared from legitimate distribution. As always, if you’re aware of something that isn’t on this blog but should be, let me know via the comments, especially if you can suggest a non-bootleg viewing opportunity. The goal remains to get to as many of these things as I possibly can. Finally, regarding the factoid in this post’s headline, the count for lifetime views of Every ’70s Movie is now over 6 million. Wow! And if you can hear that particular number without thinking of Steve Austin and his bionic sound effects, then you’re a more sophisticated ’70s survivor than I am. Keep on keepin’ on!

Thursday, June 30, 2022

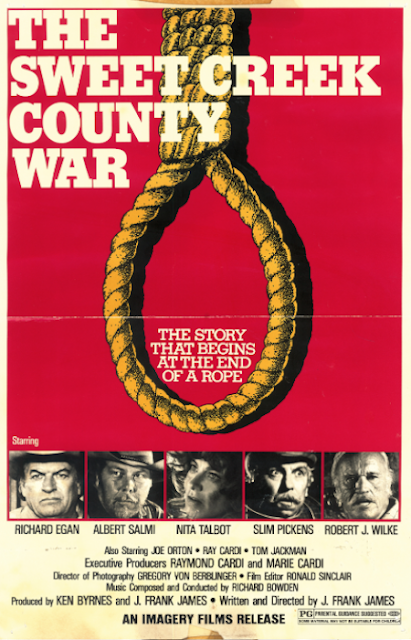

The Sweet Creek County War (1979)

As for those characters, they are retired lawman Judd (Richard Egan), aging outlaw George (Albert Salmi), and past-her-prime prostitute Firetop Alice (Nita Talbot). After Judd rescues George from a lynch mob, the men pool their resources to buy a ranch. Later, George drunkenly marries Firetop Alice and brings her back to the ranch, upsetting the dynamic of his friendship with Judd. Meanwhile, vicious developer Lucas (Robert J. Wilke), who wants the land on which the ranch is located, unleashes gunmen to intimidate Judd and George. Also drifting through the story, somewhat inconsequentially, is a stuttering dope named “Jitters Pippen,” played by Slim Pickens. (Presumably Dub Taylor was unavailable and Strother Martin was too expensive.)

The basic premise of The Sweet Creek County War appeared in countless previous Western movies and TV shows, so the picture’s only moderately individualistic elements are characterizations and the dialogue—and what these elements lack in originality, they offer in sincerity. James seems committed to exploring both an unusual friendship and the conflicted emotions of people who carry deep regrets. Accordingly, had James worked with a proper director, one imagines he could have minimized the script’s formulaic components and leaned into the poignant ones. In turn, improvements to the script and the participation of a competent filmmaker might have attracted relevant performers, no offence to the blandly competent Egan, Salmi, and Talbot. After all, acting isn’t the problem here. The most amateurish aspect of The Sweet Creek County War is unquestionably James’s artless shooting style.

The Sweet Creek County War: FUNKY

Wednesday, June 22, 2022

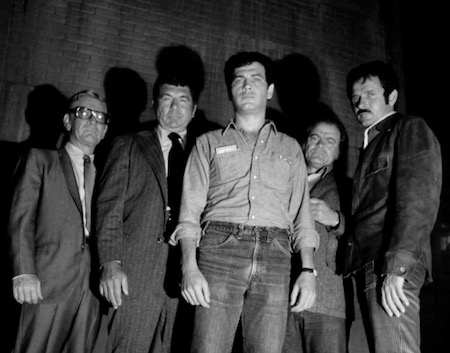

The Death Squad (1974)

Forster plays Eric Benoit, a cop tasked with identifying rogue officers responsible for vigilante killings of crooks who got off on technicalities. Although this setup prompts a handful of chases and shootouts, the main focus of The Death Squad is Benoit wrestling with divided loyalties. How deep a rot will he discover in his department? What happens when he learns that a cop who screwed him over in the past is part of the vigilante group? Will digging into the origins of the vigilante group reveal secrets that hit Benoit even more personally? To their credit, the makers of The Death Squad raise all of these questions—and to their shame, the makers of The Death Squad provide satisfactory answers to only a few of those questions. This is the sort of malnourished narrative in which the nominal female lead, played by Michelle Phillips, could have been excised from the storyline and her absence wouldn’t have been felt.

Nonetheless, the stuff that works in The Death Squad is entertainingly melodramatic and pulpy. Claude Akins, who plays the heavy, provides a potent mixture of menace and swagger. Character actors including George Murdock, Dennis Patrick, Bert Remsen, and Kenneth Tobey lend color to small roles, while the great Melvyn Douglas classes up the joint by playing Benoit’s mentor in a few brief scenes. On the technical side, the picture benefits from unfussy camerawork and a rubbery jazz/funk score in the Lalo Schifrin mode (more shades of the Dirty Harry movies). Best of all, actors and filmmakers play the lurid material completely straight, so every so often a scene—usually involving Forster—provides a glimmer of the great Roger Corman drive-in thriller The Death Squad should have been. Ah, well. We’ll always have Akins.

The Death Squad: FUNKY

Tuesday, June 21, 2022

The Strange and Deadly Occurrence (1974)

The verbose title of this mildly spooky telefilm suggests a supernatural angle, but The Strange and Deadly Occurrence is really a crime thriller with horror-flick flourishes. Approached with the right mindset, the picture provides pleasantly undemanding distraction. Robert Stack, rendering the same sort of blandly American masculinity he brought to countless movie/TV endeavors before diversifying his brand with self-parody in Airplane! (1980), stars as Michael Rhodes, the head of a small family that moves in to a new home. Soon after Michael, his wife Christine (Vera Miles), and their daughter Melissa (Margaret Willock) take occupancy, peculiar things start to happen—power outages, weird noises, etc. The family also receives persistent visits from Dr. Wren (E.A. Sirianni), an odd fellow inexplicably determined to buy their house. Soon Michael grows to believe that Dr. Wren has something nefarious in mind, unaware that a bigger threat exists.

Whereas slight narratives are often shortcomings in ’70s telefilms, less is more in this case because the focus is on atmosphere rather than intricate storytelling. Director John Llewellen Moxey and writers Sandor Stern and Lane Slate achieve adequate results while generating low-grade tension and dramatizing how the Rhodes family reacts to upsetting circumstances. The filmmakers also succeed in misdirection, allowing a third-act shift in the narrative to land with enjoyable impact. An effectively seedy performance by a familiar character actor is better discovered than described, given that his appearance is key to the third-act twist, but everyone who appears onscreen in The Strange and Deadly Occurrence understood the assignment. Costar L.Q. Jones is suitably condescending as a local lawman, Sirianni twitches well, Miles lends welcome muscle to her role, and Stack, as mentioned earlier, supplies exactly what he was hired to supply.

Does The Strange and Deadly Occurrence suffer the usual flaws of dubious contrivances and characters who make conveniently stupid decisions? Of course. But if you’ve read this deep into the write-up of a ’70s made-for-TV thriller, then warnings about such flaws are unlikely to diminish your enthusiasm. Have at it.

The Strange and Deadly Occurrence: FUNKY

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

A Taste of Evil (1971)

If a barrage of logic-bending plot twists, a handful of familiar actors, and pervasive woman-in-peril atmosphere are sufficient to hold your attention, then you’re the target audience for 1971’s A Taste of Evil, a distasteful but watchable telefilm starring two very different Barbaras, onetime Golden Age star Stanwyck and Peyton Place player Parkins. Rounding out the top-billed cast are Roddy McDowall, Arthur O’Connell, and William Windom, while the behind-the-scenes notables are prolific TV director John Llewellyn Moxey (whose career spanned 1955 to 1991) and writer Jimmy Sangster, best known for the entertainingly lurid Hammer horrors he wrote and/or directed. These folks’ assorted skillsets give A Taste of Evil a smidge more cinematic verve than the average telefilm, even though the picture is most assuredly schlock.

In a bleak prologue, a 13-year-old girl is sexually assaulted on a sprawling estate. Cut to a decade later, when the now-grown Susan (Parkins) returns home from an overseas mental institution. She’s welcomed by her mother, Miriam (Stanwyck); her alcoholic stepfather, Harold (Windom); and the family’s simple-minded groundskeeper, John (O’Connell). Susan endures several bizarre episodes, seemingly getting chased through woods, discovering a corpse that disappears in the time it takes Susan to get help, and so on. Enter Dr. Lomas (McDowall), whom the family hires to help Susan navigate trauma. Per the Hitchcockian-psychological-thriller playbook, viewers are tasked with guessing whether Susan is unwell or being gaslit—and, if the latter is the case, by whom. To Sangster’s credit, this brief telefilm juggles so many plot elements that it’s possible to overlook major clues, especially because some of the twists, once revealed, are ludicrous. (Incidentally, this was Sangster’s second pass on the same narrative—A Taste of Evil recycles a premise he originated for the 1961 Hammer production Scream of Fear.)

Stanwyck, ever the consummate professional, does her best to sell this hokum and therefore neither distinguishes nor embarrasses herself. Parkins’s take on PTSD is too glassy-eyed to register emotionally, so she’s more of a delivery device for Sangster’s yarn-spinning than a proper leading lady. And while the film largely squanders McDowall and Windom, O’Connell’s portrayal engenders a bit of empathy. Yet this is ultimately more of a writer’s piece than anything else, so it’s a shame Sangster didn’t bring his A-game; the characterizations are sketchy at best and much of the dialogue is clumsily expositional. Nonetheless, even though everything about A Taste of Evil will quickly evaporate from the viewer’s memory—save perhaps the queasy opening sequence—the flick is just cynical and nasty enough to provide a few kitschy kicks.

A Taste of Evil: FUNKY

Tuesday, June 14, 2022

The Force of Evil (1977)

Originally broadcast as a double-length episode of short-lived anthology series Tales of the Unexpected, this piece borrows the Cape Fear premise of a paroled criminal menacing the fellow whose testimony sent him to jail. (Neither the screenwriter of the 1962 movie nor the author of that film’s source novel is credited.) Specifically, in the bleak landscape of a California desert community, grinning psychopath Teddy Jakes (William Watson) terrorizes physician Yale Carrington (Bridges), who has a wife and two kids. At first, Yale feels confident about his ability to repel Teddy because Yale’s brother, Floyd (John Anderson), is the local sheriff. Alas, as in Cape Fear, the criminal studied law books in jail and therefore knows how far to push without incriminating himself. Nonetheless, things get fairly gruesome even before the first attempt on Teddy’s life—and then The Force of Evil kicks into gear by testing how violent Yale is willing to become in order to protect his family.

The juxtaposition of Bridges’ somewhat restrained performance and Watson’s menacing swarthiness generates decent tension, as do several Hitchcock-style suspense scenes. Yet the movie’s strongest mojo emanates from dramatic camera angles rendered by cinematographer Paul Lohmann, whose impressive CV include Nashville and Trilogy of Terror (both 1975). Using deep focus and low angles, Lohmann takes Dan Curtis-style claustrophobic framing to almost satirical extremes. Oh, and one last point of interest for fans of a certain age—playing Bridges’ daughter is Eve Plumb, appearing between her tenures as a member of the Brady Bunch.

The Force of Evil: FUNKY

Tuesday, May 31, 2022

The Death of Me Yet (1971)

The Death of Me Yet: FUNKY

Sunday, May 29, 2022

Death Takes a Holiday (1971)

Death Takes a Holiday: FUNKY

Saturday, May 7, 2022

Togetherness (1970)

Togetherness: LAME

Monday, May 2, 2022

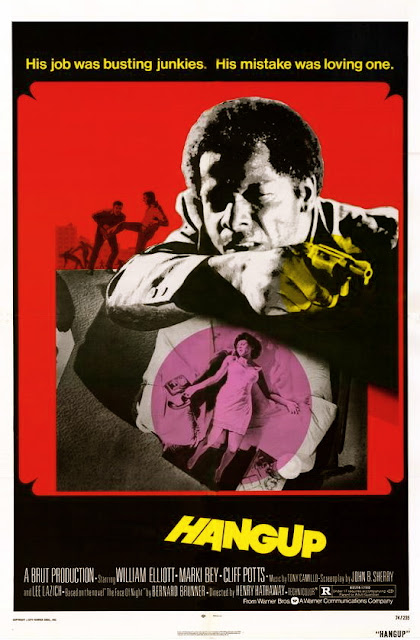

Hangup (1974)

Painfully generic blaxploitation melodrama Hangup provides a minor footnote within film history because it was the last picture helmed by Golden Age stalwart Henry Hathaway, once a reliable director of action movies and Westerns. Exactly none of his former ability is on display here—Hangup has all the momentum and style of a bad TV episode. To be fair, the version screened for this blog is an abbreviated cut that was re-released as Super Dude. Still, nothing suggests a few extra moments of character development could possibly elevate Hangup into anything meritorious, especially because the leading performances by William Elliott and Marki Bey are lifeless. He plays a college student training to be a cop (who somehow snags an undercover gig on a narcotics squad) and she plays his high-school dream girl, now lost in a spiral of drug addiction and sex work. The threadbare plot involves Ken (Elliott) pumping Julie (Bey) for information he can use to nail a big-time supplier named Richards (Michael Lerner). Predictably, close proximity causes Ken and Julie to fall in love. Tragedy ensues.

Shot in grungy pockets of Los Angeles on a minuscule budget, Hangup plods along at a dreary pace exacerbated by Bey’s and Elliott’s wooden acting. In their defense, it would take a special class of thespian to animate lines such as this one: “I’m hooked on her the same way she was hooked on smack!” Yet at least for its first hour, Hangup is moderately watchable because the hackneyed contrivance of a narc falling for a junkie has inherent drama. Alas, that strength leads to Hangup’s biggest weakness. When there are still more than 20 minutes left to go, the movie wraps up the love story, a glitch made worse because the main villain has also been sidelined. These narrative choices slow the pace nearly to the point of inertia. And then there’s the sleaze factor—or, rather, the lack thereof. Notwithstanding a few topless scenes, Hangup feels restrained in comparison to, say, Jack Hill’s gonzo blaxploitation joints. So while an easily offended viewer might find Hangup more palatable than other films from the same genre, serious Blaxploitation fans will be left jonesing for a fix of something rougher.

Hangup: FUNKY

Thursday, April 21, 2022

Every Eagles Song Podcast Interview

Friday, April 1, 2022

Wild in the Sky (1972)

After three young activists escape a prison-transport vehicle, they flee to an Air Force base and sneak into the belly of a B-52. Once the plane takes flight with a nuclear payload, the activists hijack the aircraft, thus causing havoc among military officials, some of whom are worried the crisis will expose a scheme involving misappropriated defense funds. Among the film’s characters are an uptight pilot hiding the fact that he’s gay, a radio operator who makes dirty phone calls, and a debauched flyer who suggests the hijackers aim the plane toward Hamburg so he can party in that city’s red-light district. Theoretically, any of these characterizations is workable for satirical purposes, but the movie also includes overly cartoonish characterizations, such as the U.S. president who spends his downtime zooming around in a dune buggy.

The film’s eclectic cast includes many actors familiar to viewers of ’60s/’70s TV: Georg Stanford Brown, Bernie Kopell, Robert Lansing, Tim O’Connor, etc. Yet much of the screen time gets consumed by Wynn (not coincidentally a holdover from Dr. Strangelove), and his shouting gets tiresome. Plus, in a sign of true desperation, the filmmakers enlisted Dub Taylor to unleash his angry-redneck shtick during a few scenes. Arguably, the standout performance is given by Dick Gautier (of Get Smart and many other things) because his rendition of the debauched flyer achieves Lebowski levels of chill. Alas, too much of the picture gets mired in comedy bits that don’t connect. In one scene, characters play hot potato with a grenade; in another, an officer demands that an injured soldier set aside his crutches to salute, causing the injured soldier to pratfall. FYI, Wild in the Sky was re-released as Black Jack, so don’t be fooled by the Blaxploitation-style poster emphasizing Brown after his breakout success on TV show The Rookies.

Wild in the Sky: FUNKY

Thursday, March 3, 2022

Dark Sunday (1976)

One can’t question the consistency of Earl Owensby’s earliest cinematic efforts. After scoring hits on the drive-in circuit by playing a righteous avenger in Challenge and its sequel The Brass Ring (both released in 1974), actor-producer Owensby went back to the well for Dark Sunday, in which he portrays a preacher who seeks vengeance after drug dealers assault his family. All three flicks are shameless rip-offs of Walking Tall (1973), so those seeking depth, nuance, or originality should look elsewhere. However, if the red meat of an aggrieved everyman wiping out scumbags stimulates your appetite, then consider Dark Sunday the equivalent of a fast-food meal—if you know it’s bad for you but you eat it anyway, then you have no one to blame but yourself for the indigestion you experience afterward. Crudely made in Owensby’s home base of North Carolina, Dark Sunday was nominally directed by Jimmy Huston, who helmed several projects for the actor-producer, and it was nominally written by Thom McIntyre, another E.O. Studios veteran, but every frame bears the crass fingerprints of the project’s main man, who built a fortune by peddling cinematic junk.

Dark Sunday: FUNKY

.jpg)